Choice Architecture (2) - Financial Decisions

* This is the second in article triad focused on evidence-based Choice Architecture.

In the first article, I introduced Choice Architecture and shared three examples how default options could lead to changes in healthcare at the personal and national levels. Here, I will focus on how the same concept was used in nudging people to make better savings and financial decisions by changing how the choices were presented. The examples will focus on retirement accounts and savings for future purchases.

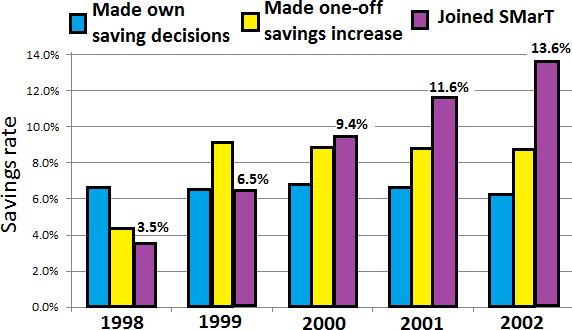

1. Retirement Savings enhanced by designing default options: The "Save More Tomorrow" (SMarT) program used defaults to increase employees’ savings rates by automatically increasing the percentage of their wage devoted to saving.

Average saving rates for SMarT program participants increased from 3.5% to 13.6% over the course of 40 months while savings rates remained stagnant in the other two conditions. This is one of the most famous nudges. Benartzi & Thaler. Save More Tomorrow, Journal of Political Economy

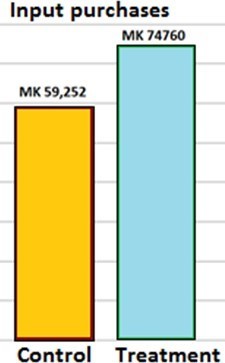

2. Commitment Devices could encourage savings: Here, two saving accounts choices were offered to farmers in Malawi: "Regular" and "Regular + Time Commitment." Time Commitment accounts allowed savers to restrict access to their own money until a designated date.

Only the commitment accounts helped farmers later to purchase 26% more agricultural inputs than the control group.

Brune et al. Commitments to Save: A Field Experiment in Rural Malawi, World Bank Policy Research Working

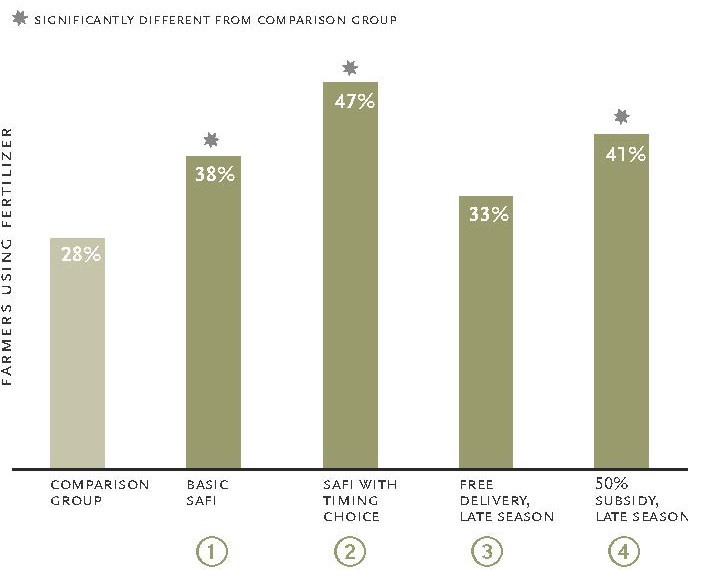

3. Choice Architecture could mitigate Present-Bias: Few farmers in sub-Saharan Africa use fertilizer. In collaboration with International Child Support (ICS), an intervention was designed to test if providing mechanisms to save harvest income for future fertilizer purchase could be effective in increasing usage. The intervention, called the Savings and Fertilizer Initiative (SAFI), would help Kenyan farmers mitigate Present - Bias.

- Basic SAFI: An ICS officer visited farmers immediately after the harvest, and offered to sell them a voucher for fertilizer, at the regular price, with free delivery later in the season. The farmer had to decide during the visit whether or not to participate in the program, and could buy any amount of fertilizer.

- SAFI with ex ante Choice of Timing: An ICS officer visited the farmers before the harvest and offered them the opportunity to decide when, during the next growing season, they wanted the officer to return to offer them the SAFI program. They were then visited at the specified time, and offered a chance to buy a voucher for future fertilizer use.

- Free Delivery Visit Later in the Season: Same as SAFI program, but farmers were visited later in the season. An ICS officer visited farmers 2-4 months after the harvest when it is time to apply fertilizer as a top-dressing to the next crop, and offered them the opportunity to buy fertilizer, at the regular price, with free delivery. This program was identical to SAFI, except that it was offered later.

- Subsidy Later in Season: An ICS officer visited the farmers 2-4 months after the harvest - when it is time to apply fertilizer to the next crop - and offered to sell them fertilizer, at a 50% subsidy, with free delivery.

In the first season, the program increased fertilizer usage by 14%, on a base of 24%. In the second season, the increase was up to 18%, on a base of 26%. SAFI with ex ante timing choice was also successful, increasing usage by 22%.

Duflo et al. Nudging Farmers to Use Fertilizer : Theory and Experimental Evidence from Kenya, American Economic Review

As with the first article, my goal here is make us think if there are small changes that we could implement at our work places to navigate hard-to-change organizational, management or leadership behaviors.

* * *

* I am grateful for the publications from the Stirling Behavioral Science Centre; they inspired the writing of this article triad.